What hell (probably) smells like

October 14, 2025

Among the torments described in sacred and ancient texts, smell—one of the most primal and emotional of human senses—rarely receives direct attention. For odor exorcists such as ourselves, it’s the component of the sensory human experience we are chiefly concerned with.

Likewise for ancients, odor was intimately tied to morality, purity, and the divine. Fragrance (naturally derived, of course) was the essence of heaven; stench was the signature of decay, death, and sin. If we imagine the olfactory reality of hell, we can reconstruct it not from poetic fancy alone, but from biblical hints, apocryphal visions, and the sensory imagination of antiquity.

Sulfur and smoke: the biblical core

The most enduring image of hell’s scent comes straight from scripture: the “lake of fire and brimstone.”

In Revelation 19:20 and 21:8, the damned are cast into a place burning with brimstone—an archaic word for sulfur. The Hebrew Bible also associates sulfur and fire with divine judgment: Genesis 19 recounts how Sodom and Gomorrah were destroyed by “fire and brimstone from the Lord out of heaven.”

For those who are familiar with battling the satanic scent left by rotting eggs, that’s precisely what sulfur smells like. Imagine an eternity spent in a dark and hot place with nothing but rotting eggs wafting into your nostrils. Yuck!

Ancient people knew the smell well: sulfur deposits near volcanic vents and salt lakes gave off fumes that were thought to rise from the underworld itself. To the biblical imagination, then, the stench of brimstone was not merely unpleasant—it was the scent of divine wrath, the tangible breath of corruption and punishment. Isaiah 30:33 describes Topheth, a valley outside Jerusalem associated with child sacrifice and later identified with hell (Gehenna), as a place whose “pile is made deep and large, with fire and wood in abundance,” kindled by “the breath of the Lord, like a stream of brimstone.”

Hell, by this reasoning, would smell like an eternal chemical fire—an acrid mixture of sulfur, smoke, and scorched flesh.

Gehenna and the stench of refuse

The New Testament’s dominant word for hell—Gehenna—is not an abstract realm but a real valley outside Jerusalem: the Valley of Hinnom. In the centuries before and after Christ, this place was a site of shame, said to have hosted human sacrifice to pagan gods, and later became a dumping ground for refuse and the bodies of the condemned. Fires burned there constantly to consume the waste.

The olfactory implications are striking. Ancient Jerusalem, without modern sanitation, would have known Gehenna as a place that stank of burning garbage, decaying flesh, and smoke. The metaphorical transfer from that reeking pit to the eternal fires of damnation was natural. When Jesus warned that it was better to lose a limb than to be “cast into Gehenna,” his hearers would have understood the smell as vividly as the flames. The horror was not only moral—it was sensory. A bottle of Odor Exorcism would have come in handy right about then!

The odor of sin and the aroma of holiness

To the ancient mind, moral and spiritual realities were sensed through smell. The righteous were said to possess a “sweet savor” before God; the wicked emitted a stench of corruption. In 2 Corinthians 2:15–16, Paul contrasts the “aroma of Christ” that brings life to believers with the “odor of death” that clings to those who perish.

Early Christian and Jewish traditions extended this metaphor literally. The souls of saints were described as exhaling fragrance upon death, while sinners’ corpses emitted foul odors. The Apocalypse of Peter (2nd century CE) paints hell as full of “stench and corruption,” where “worms crawl without rest.” Likewise, the Vision of Paul (3rd century CE) reports that the damned “gave forth an unendurable stench,” a punishment as much olfactory as physical. Medieval visionaries later elaborated on this: in Dante’s Inferno, each circle of sin has its own unique miasma—the boiling pitch of fraud, the fetid swamps of wrath, the icy fog of treachery.

For the righteous, fragrance was proof of sanctity. The relics of saints were said to exude odor sanctitatis—a miraculous sweetness defying decay. Thus, to the medieval Christian, the smell of hell was the absolute opposite of divine presence: where God was fragrant, Satan stank.

Ancient near eastern and Greco-Roman echoes

The Hebrew and Christian imaginations were not alone in associating the underworld with stench. In Mesopotamian myth, the land of the dead—Irkalla—was a place of dust, rot, and polluted air. The goddess Ereshkigal ruled over a realm where the dead “eat clay and drink dirty water.” Odor here symbolized separation from life itself.

Similarly, in Greco-Roman tradition, the rivers of Hades—especially the Styx and Acheron—were believed to reek of sulfurous vapors. Writers like Virgil and Seneca described volcanic vents in southern Italy (such as the Phlegraean Fields) as literal gateways to the underworld, their smoke and smell serving as proof. The Avernus crater, thought to be an entrance to Hades, was so fetid that birds supposedly fell dead from the air above it.

To breathe the air of hell, then, was to breathe death made tangible—a noxious, suffocating inversion of life’s fragrance.

The alchemy of fire, flesh, and fear

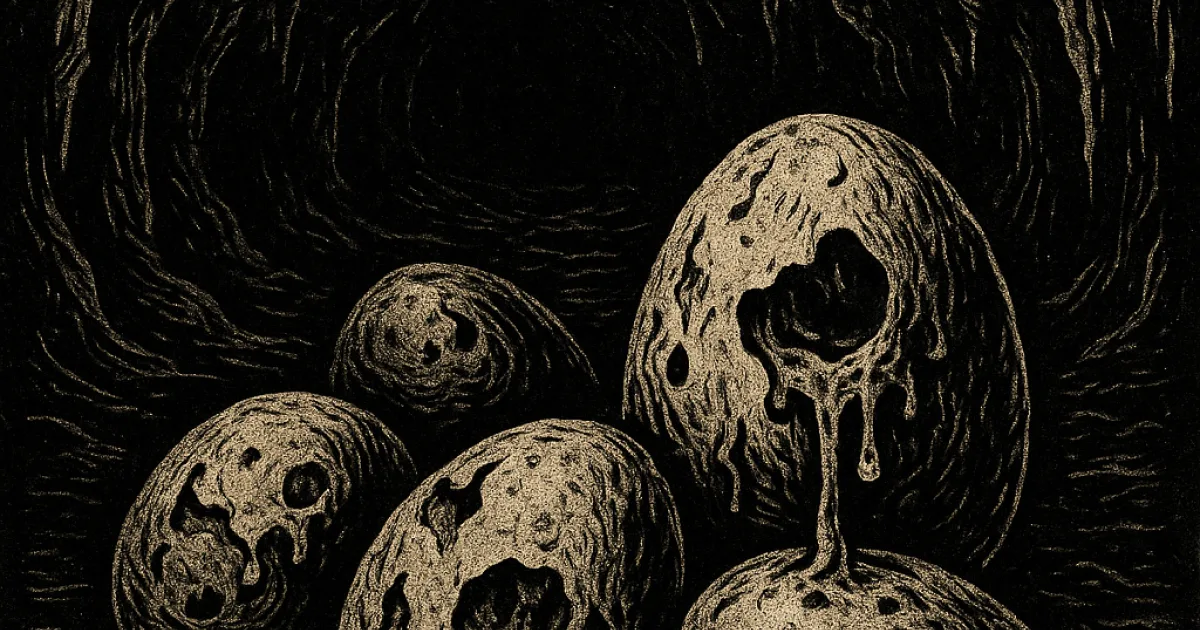

If we combine these strands—the biblical brimstone, the refuse of Gehenna, the metaphors of moral decay, and the volcanic imagery of antiquity—an odoriferous image of hell emerges. And there isn’t enough Odor Exorcism in existence to quell those fires.

The dominant notes would be sulfur, burning pitch, and charred flesh. Secondary layers might include the sweet-sour reek of decomposition, acrid smoke, and the stench of stagnant water or excrement—elements found in apocryphal and medieval visions alike. The air would be hot, heavy, and unbreathable. It would cling to the skin, saturate the lungs, and corrode the senses—a smell not only detected but suffered.

Yet beyond its physical horror, the smell of hell in ancient thought was symbolic. Odor marked the boundary between the living and the dead, the pure and the profane. In this sense, the “stench of hell” is the sensory manifestation of spiritual corruption—a smell of separation from God, of being cut off from the breath of life itself. In other words, the opposite of a clean and fresh home environment.

Conclusion: the theology of stench

For ancient peoples, smell was theology in vaporous form. The faithful offered fragrant incense to signify prayer rising heavenward; the damned exhaled sulfur and decay as the inverse of holiness. Hell, in biblical and classical imagination alike, was not just hot—it was foul. Its stench embodied the physical and moral decomposition of souls alienated from divine light.

If heaven smelled like frankincense, lavender, and myrrh—the fragrance of holiness—hell smelled like sulfur and smoke, like the pit of Gehenna, like the breath of everything unclean. It was, and remains, the odor of absence: the smell of a world where nothing living breathes.